Sustainable infrastructure's 'historical moment' needs tech

The federal Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund (GGRF) will have a transformative effect on sustainable infrastructure across the United States. But connecting this $27-billion influx of capital with the projects and communities that need it most will require lenders to rally together and build new frameworks.

Gwen Yamamoto Lau put it plainly during a Banyan Infrastructure webinar last week: “It's going to take a village to achieve our climate goals, so every lender is invited to join the party.”

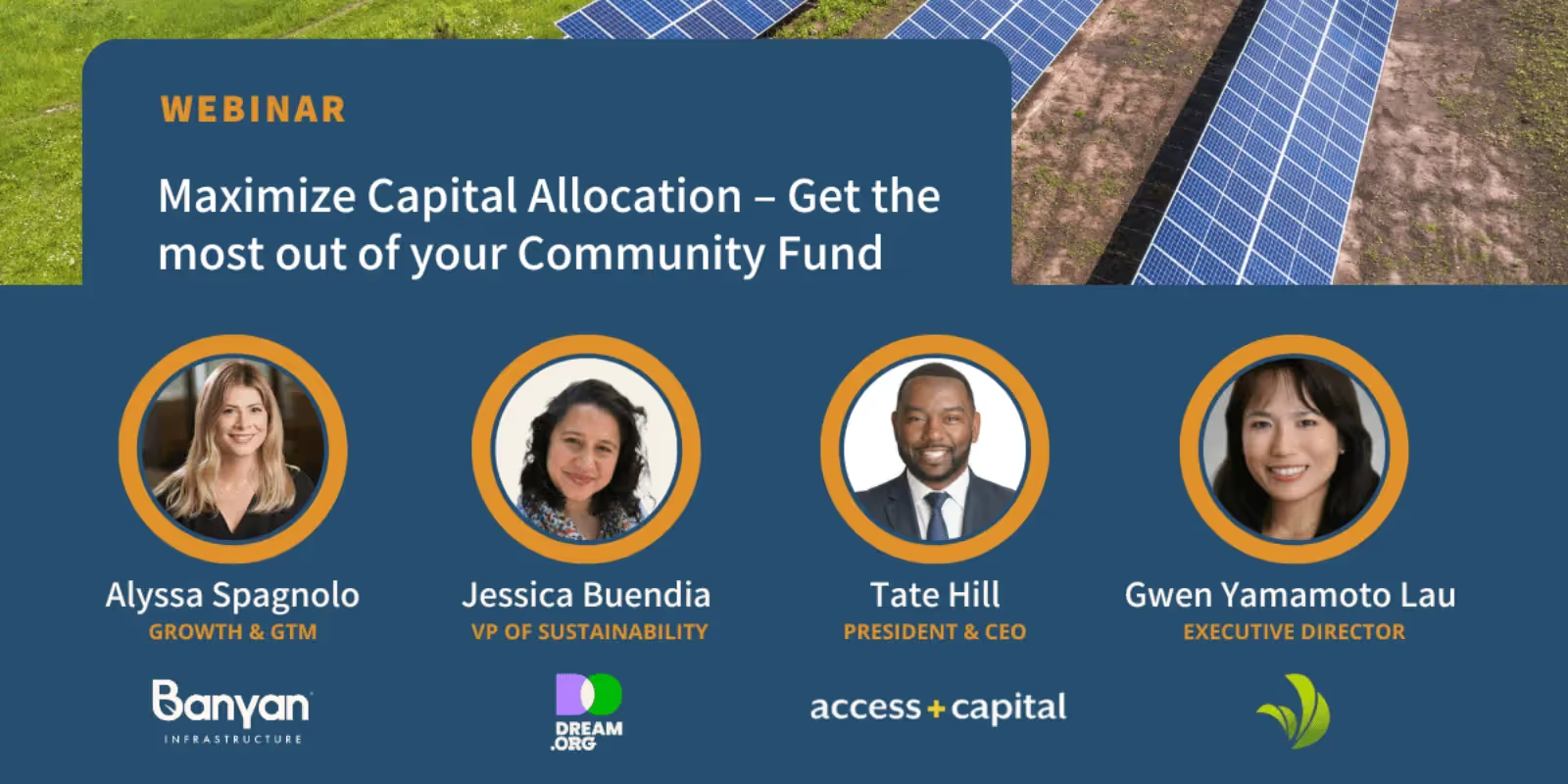

The executive director of the Hawaii Green Infrastructure Authority was joined by a panel of others eager to maximize the opportunities of the GGRF, including Tate Hill, president and CEO of Access Plus Capital, and Dream.org vice-president of sustainability Jessica Buendia. The panel, held on March 20, was moderated by Banyan’s own head of growth and strategy, Alyssa Spagnolo.

Throughout the hour-long webinar, titled Maximize Capital Allocation: Get the Most out of Your Community Fund, the panel covered a range of topics, from the state of community lending today to the promise and potential challenges presented by the GGRF, the practical solutions needed to overcome these issues, and each panelist’s vision for the future of sustainable infrastructure investment.

Here are the top-line takeaways:

More money, more paperwork

This federal program, administered by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), aims to direct billions of dollars into renewable energy and sustainable infrastructure project finance. Its overall goal is to kick-start investment, especially in underinvested communities that have faced hurdles to accessing clean energy and other benefits of the transition to a net-zero economy.

If done right, the GGRF won’t just benefit American communities today, it will pay off for decades to come. That’s because the program aims to not just hand out but recycle capital, Alyssa explained. While this promising, once-in-a-generation opportunity will direct funding to exponentially more projects, it will also require exponentially more layers of compliance and reporting than ever before.

“Without a layer of digital infrastructure, this is really hard to do and really hard to standardize,” she said. Banyan Infrastructure’s project finance software is designed to “enable for recycling of this capital,” but to build an effective, efficient system for capital deployment, project financiers need “to start with creating the standards to improve liquidity and improve the processing time, and really the co-ordination that this is all going to take to come to life.”

A ‘new terrain of stakeholders’

Once GGRF recipients are announced — which should happen any day now — the entire cast of ecosystem players will need to hit the ground running. Green banks, CDFIs, community lenders, nonprofits, and other organizations must quickly scale up, build capacity, hire additional personnel, and align with the EPA on how to work with both other recipients and the federal agency itself, Jessica pointed out.

This is no easy feat for community-based organizations where leaders are often “holding many, many hats,” she added. All three panelists agreed capacity is a major challenge for these organizations as they try to keep up with government timelines and manage reporting requirements with limited resources.

Then there’s the challenge of scale. For many community lenders, the size of the GGRF is well beyond what they’re used to thinking about when it comes to financing. This larger capital flow will require those lenders — and the communities they serve — to understand new regulatory spaces and build relationships with bigger players.

“You're really thinking about neighborhood-scale — if not municipal-scale — infrastructure solutions. And what this means is that we're throwing front-line communities into significant partnership work that requires navigating local government structures, that requires working with different kinds of partners, navigating utility frameworks that people are unfamiliar with,” Jessica explained.

“If you've historically come from housing or workforce development or entrepreneurship, this is an entirely new terrain of stakeholders that you have to be corresponding and navigating with on a regular basis if you want to be at the table. And again, if you don't have the capacity to, then it's really hard to enter into these conversations and to be thinking about these large-scale solutions.”

Tech to drive projects — and standards — forward

Taken together, these challenges of capacity and scale mean project finance systems must create more efficiencies so community lenders can keep pace with the GGRF. The EPA estimates reporting requirements will cost anywhere from 44,700 to 604,000 hours and $4.8 million to $32.4 million per year for the next three years, depending on the program.

Failure to meet these requirements puts the success of the GGRF in jeopardy. But organizations are leveraging the partnerships they already have to help them scale quickly, Tate said. Existing resources are allowing Access Plus Capital to ramp up fast so “we're not having to reinvent or create either technologies or platforms,” and doing so in a way “that enables us to deploy the capital that meets all the regulatory and reporting requirements.”

One such resource is Banyan Infrastructure’s project finance software, which collects and manages data in one secure location, providing visibility and access for stakeholders while cutting down on the time spent performing basic data-entry tasks.

Gwen echoed the benefits of such software in her own work. “We want to just have data inputted one time, and that is from the application that goes through our underwriting, that goes through our documentation, and so on,” she added.

Beyond data collection, project finance software can also begin to create tools and standardizations that help to streamline deal-making processes and empower those who require technical assistance to drive projects forward. Jessica highlighted Dream.org’s project readiness assessment, a report that produces actionable checklists and next steps for community groups seeking to implement sustainable infrastructure projects.

“For a lot of the nonprofit sector, these are all new ways of being able to understand their value in regards to making the world a better place and what that actually all looks like,” she explained. “I think more of this kind of technical assistance, but that is really about partnering with communities where they're at, is needed across the field.”

A new future for sustainable infrastructure investment

Across the panel, there was a consensus that the GGRF marks a chance to ensure sustainable infrastructure finance works for everyone in every corner of the country.

Tate pointed to Opportunity Finance Network, a leading CDFI trade organization that’s been pushing to ensure clean and green lending “become a part of the fabric of our overall lending,” incorporating such considerations into technical assistance, coaching, and access to funding as well as developing financial products.

“I think there's been a huge interest In our industry about making sure that as we think about this work, it's not like this special project — this is so critical to how our communities are going to thrive going forward,” he said.

For Jessica, philanthropic organizations like hers are entering a new era where embracing sustainability isn’t just about building physical infrastructure but developing the financing mechanisms behind it, too.

“A lot of people who go into this work to do good for the environment, or to do good for marginalized communities, are not always trained to also build sustainable business practices that can have revenue models that will sustain the work in perpetuity or over long periods of time,” she explained. “That is something that the nonprofit sector as a whole is going to have to address.”

Though there are plenty of challenges to address in the short time frame of GGRF deployment and beyond, she remained optimistic about the impact a federal fund like this could have on tackling inequities in the United States.

“We have this incredible historical moment to be able to right some wrongs from the past,” she added. “Where redlining has been such a centerpiece of the financial industry story in the U.S., we actually now have the potential market conditions to turn that around, to be able to actually make disadvantaged communities the green-lined communities of choice where investors actually want to come and be able to leverage these federal funding opportunities.“